by Yuanhang Sun

Miao Jina is an independent screenwriter and filmmaker. She was born and raised in Shanghai, with an MFA in Directing from the American Film Institute. Her works focus on marginalized groups during the huge societal change over the past decades in China. Her projects have been selected for prominent film platforms such as the FIRST International Film Festival and Shanghai International Film festival, gradually gaining wider recognition within the film industry in China.

Q: Could you start by introducing yourself?

A: My name is Miao Jina(缪吉娜), and I’m an independent screenwriter and director. I did my undergraduate degree in Radio and Television Directing at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, and later received my MFA in Directing from the American Film Institute. I graduated three years ago, and since then I’ve mainly been developing my first feature film project. So far, I’ve written two feature scripts, shot two sample reels, and I’m currently in the early stage of seeking investment. I’ve also taken part in project markets and talent programs at several domestic film festivals.

Q: How did studying in China and then AFI shape you?

A: I think my undergraduate and graduate studies were two stages that complemented and balanced each other very well. Shanghai Jiao Tong University gave me a broad education in literature, communication, new media, and film production. This broad education gave me a solid foundation of knowledge.

At the same time, because it is a comprehensive university, our training in practical filmmaking wasn’t highly specialized. We did make some short films, but it was usually just classmates forming small groups, picking up a camera, and asking friends to act.

AFI, on the other hand, was a completely different approach. It’s a highly specialized school focused solely on film production. For me, as a directing fellow, I directed four projects during my time there, always in the role of director. That gave me the chance to work within a team where everyone had a clearly defined responsibility. I think this was invaluable training for a professional director.

Of course, AFI was also a great platform. It brought together people who were determined to pursue careers in the film industry. Even now, after returning to China, I’m still part of the AFI alumni community, where we share resources and support each other.

Q: Was it difficult returning to China after studying abroad?

A: I do feel there’s a kind of gap—or even a barrier—when you study abroad and then come back to work in the Chinese industry. Students who graduate from domestic film academies can often connect with industry resources much faster. They have professors, alumni networks, and senior classmates who bring them into the industry. But when you come back from abroad, everything feels more unfamiliar. For example, when I had just returned and wanted to shoot a short film, I felt completely lost.

Over the past three years I’ve been continuously participating in film festivals, project markets, and various development programs, hoping to build closer ties with the industry here.

Q: Speaking of film festivals, I know you participated in the FIRST International Film Festival. What was your impression of the FIRST platform?

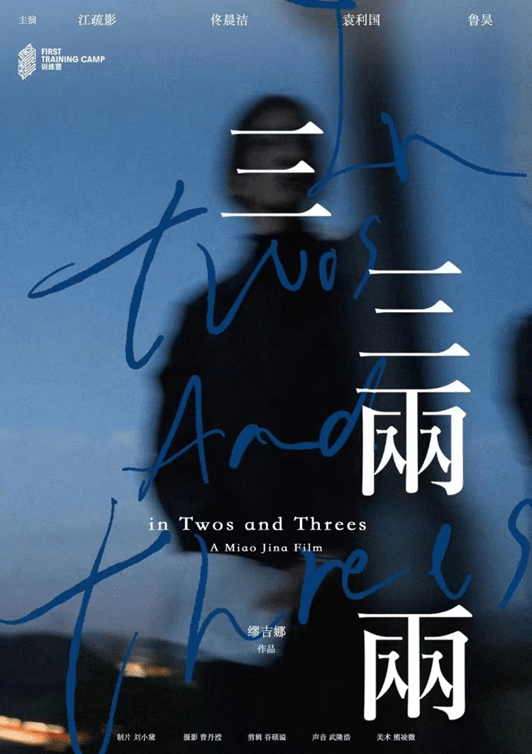

A: My experience at the FIRST Training Camp was really positive. The training camp acted as a platform that brought people together. For example, when I made a short film during the camp, I received support from the organizers in many ways.

One big difference was in casting. If I tried to approach actors on my own, no one had heard of me, and established actors probably wouldn’t agree to work on my short film. But once FIRST was involved, actors who trusted the platform were willing to collaborate. During the camp I was able to work with Jiang Shuying and Tong Chenjie—both highly accomplished actors in the industry. Without FIRST, they likely wouldn’t have agreed to appear in my short.

I think many film festivals and labs serve a similar function. It’s not necessarily that you lack ability, but without a platform like this, your ability may not be seen or acknowledged. These platforms give young filmmakers that visibility and credibility.

Q: Can you tell us about your feature projects?

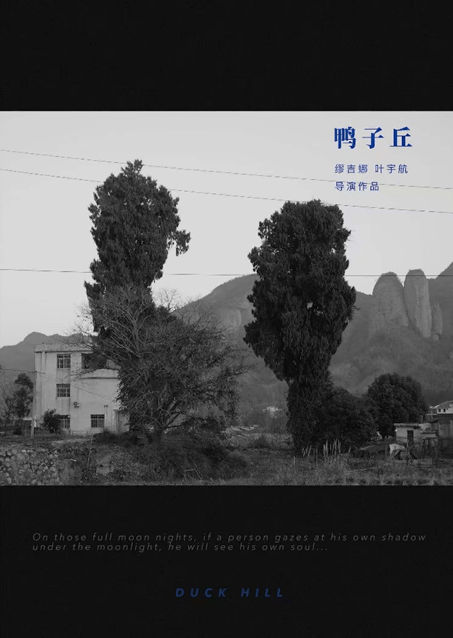

A: I have two feature projects in development. My latest project in development is called Duck Hill. It’s set in a rural environment but incorporates elements of fantasy. The story takes place in a small mountain village in Jiangxi Province and focuses on the lives of marginalized individuals there. It also weaves in some fantastical elements—such as mountain spirits and full-moon rituals. What I want to explore is the inner spiritual worlds of people living in these marginalized rural communities.

Developing a feature is never something that can be finished quickly—it’s more about which project finds the right opportunity at the right time. Most of the time isn’t spent sitting at your desk writing, but rather in searching for the right resources and funding.

Q: For emerging directors in China, what do you think are the main challenges?

A: I would say the market. The industry isn’t as strong as it was a few years ago—many films released in cinemas are actually losing money, and box office results are often disappointing. Production companies are now much more focused on projects with clear market potential.

As a young director, I used to care more about creating films with a strong personal voice. But once you start dealing with production companies and the market, you realize what most of them are really looking for are projects that can generate strong commercial returns.

A few years ago, there was more funding in the industry, and investors were more willing to take risks on emerging directors. But now, there’s less money overall, and what remains is concentrated in fewer places. As a result, the number of people who actually get the chance to make their first feature is shrinking.

Q: Any advice for film students who studied abroad and are now planning to return to China?

A: Everyone has different aspirations. Some people hope to land a good job at a company after graduation; some want to make commercially successful films; others want to focus on developing their own voice as an auteur. I think it’s very important to be clear about which path you want to take. The earlier you figure that out, the fewer detours you’ll face.

At the same time, it’s not something you can fully predetermine—it’s a process of change. What you want when you first arrive abroad may be very different from what you realize after you’ve actually created a few films. For instance, when I first went to the U.S., I imagined myself entering the film industry’s professional system. But after making a few shorts, I realized I’m more inclined to pursue authorship and personal expression.

So my advice would be: try to clarify what you truly want as early as possible.

Q: Could you share a few films you really love, and why?

A: One is Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha. I’ve always loved that film because of the way it portrays its protagonist. She feels so sincere, very idealistic, not socially savvy, flawed yet genuine.

Another is Happy as Lazzaro by Alice Rohrwacher. She’s simply a genius—her work is full of spirit and profound philosophical reflections, but presented in a way that feels simple and natural.

I also really like Sean Baker’s Starlet. It tells the story of a young woman working in the porn industry. What impresses me is how fresh and delicate his style feels, even when the subject matter is controversial.

Another director I admire is Carla Simón. I recently watched her film Alcarràs, about a family of peach farmers whose orchards are cut down as the village develops. Her films feel incredibly natural and delicate.

And finally, from Hong Sang-soo, the film I love most is On the Beach at Night Alone. Among his many works, that one stands out to me for its inventive narrative structure.

Leave a comment