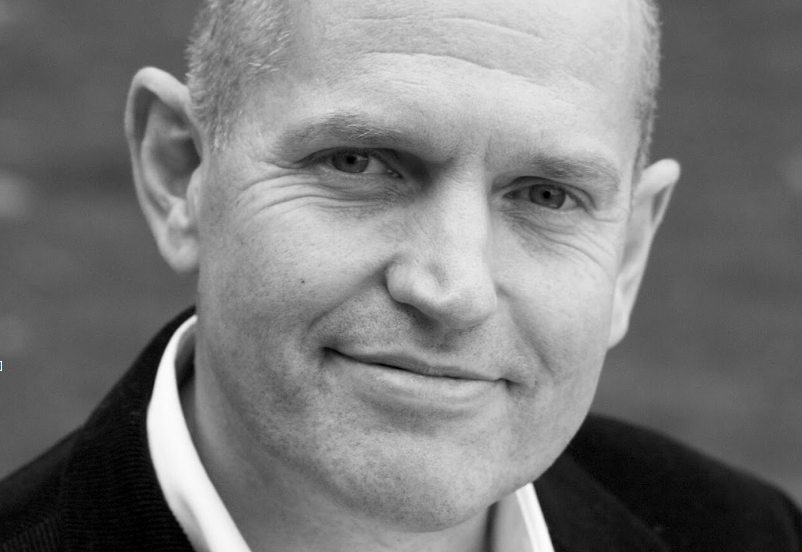

Playwright, screenwriter, actor – and Bafta-winner – Tim Whitnall spoke to Holly Coley about a lifetime of making it as writer, one gig at a time.

What got you into this world of writing?

I loved being in the big dark room with lights, in things like the Cub Scout reviews, where you got to sing and dance a bit. I never forget that feeling of turning to face this barrage of lights and fear. It was the roar of greasepaint, you know, I could smell it, it smelt different up there; the look, the heat, the noise.

I don’t know if I got the bug then but it was certainly quite a visceral feeling. About two years after that I auditioned for a show, to this day the only job I ever did as a performer that I was given on the spot. It was in the West End, it ran for two years and won an Evening Standard Award for Best Musical. I guess I knew that I wanted to write, even when I first came to London, but I didn’t for about 10 to 12 years after I started performing. I started to meet people I could ask whether or not they’d give me a chance to contribute a line here and there. My breakthrough from that was when I worked for a man called Peter Murphy, a producer at Central Television. And I owe him my life really. Apart from being a lovely man, he set up (with a woman called Sue Nott) this brilliant thing called the Junior Television Workshop. They gave me the opportunity to write for young performers. Learning the craft is something that I think you can only really do by being in the game. I look back now I cringe and I think “oh gosh, what was I writing?” But it was still honest writing.

So I was really lucky. I worked in TV, I worked in radio, I worked in film and I worked in theatre. All the time, I was learning, until I decided to do it full time, in 1998. I chose that, it might have been a big mistake. It’s certainly nowhere near as lucrative as what I was doing but it doesn’t matter, I’m doing what I truly love doing. And that’s vital, you know, if you’ve got that passion and the opportunities are commensurate, the world is your lobster.

It’s very reassuring to hear you say you look back at things and cringe about them now. As an actor, do you find that that does also inform how you write? Does it help?

Yes and no. I think it does from a dialogue point of view. One thing is that I do love writing for certain actors. I’ve just written a short film called The Choice and the producers cast the wonderful Alex Macqueen, who’s Neil’s dad in The Inbetweeners, and in The Thick of It – he’s an instantly recognisable TV face. I’d written a play for Alex called The Sociable Plover that became a film called The Hide and if you fancy a scary watch, watch Alex in The Hide – he’s wonderful. And I can hear him as I write his dialogue. I know his face. I know his thought processes. I’m sure you’ve learned this on your course – character equals plot in every single case. It absolutely does and from that all those synapses from your character be it dialogue, their walk, their worldview, their politics, their prejudices, their fears, their hopes – all that stuff comes from character. So yes, sometimes I do think the acting helps. There are many, many more times when I don’t have an actor to write for. But I somehow picture somebody either saying the dialogue – somebody like that person that I can imagine. But principally, once you’ve got a character, that informs dialogue.

What would be your lessons learned that you would pass on to new writers?

I think the first thing I had to learn was to accept criticism. That’s twofold really, it’s criticism of your peers, whether they are your producer, your director, your actors, who you’re writing with – industry criticism. And then there’s the criticism of critics themselves.

I had a really great success in Edinburgh last year with a show called Lena that I loved working on. We had some stellar reviews for it. But I talked to other performers who had been lacerated by critics and reviewers. I was so pleased to find that Phoebe Waller-Bridge had written an open letter of sorts to young writers and performers – she printed a two star review of fleabag that she had received when she did the original performance in Edinburgh. She was saying, “Look, I got pulled apart by this particular critic. Doesn’t matter. Look what’s happened to that piece” and I think that was really consoling. I have had five star reviews and on the same production two star reviews and it hurts. But you have to learn.

People who are there to help you are doing so with an objectifier, because they want you to win. They’re not doing it because they think they can write it better or you should write it differently. Some of the best notes I’ve ever received are the toughest. I remember one producer saying to me, “flip the character, make him a her” and it totally opened up the play and it was a brilliant play because of it. Some script editors are brilliant at this. I remember when I wrote Best Possible Taste, I was really lucky to work with the great Ben Stephenson, commissioning editor for drama at the BBC (before he left to do wonderful things with J.J. Abrams). I’d written that as a three act drama. The protagonist, because he was the victim of HIV, I’d written the last act in which you see that decline all played through hospital monitors, because Kenny Everett used visual monitors as a kind of metaphor for things. Ben just said, “cut the third act, just leave him looking forward”. It worked brilliantly. And somebody like Ben, they’ll give you notes like that, that will not just sell the project, they’ll make you a better writer. I know a lot of writers who are obdurate, quite stubborn, unyielding. But I think it’s a collaborative project. You’re working with people. I’d much rather see my project made than have it sit on a shelf with everybody telling me how brilliant it is.

So apart from accepting criticism, I would say, just learn to cooperate. I very rarely resist a cut because you can always put it back in. Another director told me that, Neville Green – I used to do a kid’s series and he just said “there’s no such thing as a bad cut”. And generally speaking (I’m sticking my neck out here) you don’t put it back in. I don’t know why, you don’t. Chris Chibnall, who wrote Broadchurch, was a Doctor Who showrunner, went on record as saying it’s really difficult and it is difficult. And there are days when you sit – I’ve been writing all day today – and you sit and think and think. Unless you’re co-writing, there’s very little collaboration at the coalface. It can be a very lonely process. Not sad, but just singular, solitary. But enjoy that frustration a bit as well – when I get a screen and it’s absolutely blank, I know that by six o’clock (which is where I normally work to), there will be something on it. It might not be right, it might not be ultimately where it ends up, but it’s something – it’s a diagram of possibilities.

Again, that’s so reassuring because I think a huge part of what the process of the course is trying to stress to us is that criticism is a good thing.

Yes it can be constructive. Should be constructive. And it can be very positive. I remember when I was young, I was in a production of Godspell at the Old Vic Theatre, and there was a legendary theatre critic, Michael Billington, who used to write for the Guardian. Billington said: “for those of you who missed the original production of gospel, here’s your golden chance – to miss it again.” Now, I think that’s hilarious. But when I was 20, I’d sit there going –

[Tim mock sobs]

My absolute highlight was to see it in Dame Diana Rigg’s brilliant book (if you can get hold of it, you must get it). It’s a book of legendary theatre reviews and it’s called No Turn Unstoned. It’s actually reprinted in that, so I consider it a victory now. But I didn’t at the time. It can be really, really eviscerating, really quite personal as well. I wrote a play that was at the Old Red Lion in Islington in 2006 and one of the local reviewers from the Islington Advertiser or something, described my play as an “effort”. We did 100% business, the audience loved it. I think that’s interesting, that disconnect between an audience hit and a critical hit. I watched the excellent documentary on Noel Coward. Of course, a polymath and a brilliant writer, he was asked, “What is the meaning of success to you?” “Two Words – Box. Office”.

For me, I think it differs really from production to production. I think all kinds of things, from giving people opportunities, creating work for them, a happy company, the sound of a laugh or a gasp; so much of it, I think, equates to success. As a writer, your responsibility is solely to deliver the best possible piece that you think absolutely evokes your vision. Something that performers are going to want to perform, the characters are engaging and accessible. When the house lights go down and here we go – which is a terrifying moment – but by the end of it, I know the audience will react like this. And that’s what was so great about Lena. It’s a very tragic story about a young performer who fell victim to anorexia nervosa, but my absolute thrill was to see a man in an Iron Maiden t-shirt standing up at the standing ovation at every show. He stood up at one show with tears rolling down his beer belly. I thought, well, sometimes you get it right. Sometimes you write something great, and then you’ll write four or five that come and go. Or you write one that’s an absolute stinker and then the next one will be alright. It is a wave and you constantly have to encourage yourself to think as long as you’re doing it, it means you’re part of our industry. You’re delivering and coming up with new ideas and pulling down light bulbs. I always say to my partner, “I’m pulling a living out of thin air!” but it is a bit like that. Because where else would you have to sit and face a blank thing? You write something that, what Eric Morecombe used to call “a living, breathing, paying audience”, are going to come see.

That was a huge question I had – where do you find that motivation in the low points to carry on?

I nearly said Guinness but that would cheapen it (I don’t drink a lot). I would say that I have a really supportive partner. She’s also a theatre producer so she knows what it’s like. She is the High Priestess of tough love but I know she deeply deeply cares about what I do and who I am. I think the support of dear and trusted friends and I mean that – trusted. You know the ones – the maps – you can trust. They might not always tell you what you want to hear but I think that taps into my earlier response about criticism. My partner runs Feather Productions with me. She’s the best reader I’ve ever known. It is a real innate talent, I’m hopeless at it. But she studied film and she will say, when you’re watching something, “that will happen” within the first five seconds of watching any film. She can read a script and then bring into that process a level of criticism that I really trust.

I also have a great agent at Independent Talent who, again, doesn’t love everything I do, but he gives me just the right amount of encouragement to say “there’s something here, chase it down. We’ll get as far as we can with it.”

So in answer to that question, which is a brilliant question: I just keep going. There’s no real surefire, scientific proof of this being a good thing for me, I’m sure it creates many problems. Gosh, insomnia and nights of real doubt. Often you can write – I mean, this sounds pretty mercenary – you can write and be paid to write and your project never sees the light of day. And I’ve always found that quite frustrating because, like the great painter who said that the purpose of painting is in the decoration of walls, I think the purpose of writing – apart from fulfilling your creative aspiration – is that I want people to see it or read it or hear it or laugh at it or hate it! You can care with passion called hate – I don’t mind if an audience hates but as long as it engenders some sort of visceral reaction.

The last few months were a bit of a blur, and I kept reminding myself that it was okay to take a day out or to go birdwatching or to see my friends again. It’s really important to remember that an awful lot of good comes from stepping back from it sometimes. My brother will tease me “it’s not like going down a mine” (and I always joke “ever written down a mine? I have”). It isn’t, but it’s a very different form of energy and a very different form of application and of work. I don’t think it’s an age thing, but I’ve also always found it quite tiring. It’s almost as if it pulls something out from you. For example, The Sociable Plover – it’s always performed because we’ve had hundreds of licences go out and it’s lovely – everyone asks me “which of the two of the two leads in it are you?” and I’m all of them. It’s such a truism but when you think about really successful shows, they come from people that know what they’re talking about and know what they’ve experienced there. I think maybe that’s why I can write up a lot of biopics set in show business. Because I’ve walked that walk and I’ve seen those characters. And like any other precinct to drama, it is a workplace. Workplace dramas are great. So I would say, I plug on, I never rest on my laurels, I never live in the past. In fact I said the other day, I don’t think I’ve even enjoyed looking back at what we did last year. I just kept going.

So how do you get ideas in general? Do they just come to you?

Yes, sometimes they come. Quite recently I was in Cornwall in a wonderful crumbling little harbour called Portwrinkle. And I walked across the beach and there was a sign saying Finnygook. I thought that’s the most wonderful word, Finnygook, no idea what it was. It was an arrow to a beach and it was an old smugglers beach. And I uncovered this true story about a smuggler back in the 18th century. He came to a decidedly gruesome end when he grassed up his mates. They threw him down a well, and to this day, it is said that his ghost haunts the moors and the lanes around Portwrinkle Cove. I thought if I could combine that with a contemporary story, in which I place somebody in isolation, then perhaps there is something that I could do with this story. So I’ve just submitted it to a theatre company as a pitch document. The pitch I find is even harder, because every word counts. Most writers feel like this because you’ve got to basically come across very quickly in something that somebody bites or doesn’t bite on.

But something like that came just purely by chance of a lovely little New Year break in Cornwall. There are other things that you see or listen to and you think, “wow, no one’s told that story before.” Whether it’s historical – if I can give you an example, something like the Lockerbie air disaster. I know of three creative projects right now that are greenlit about that project. The Emily Maitlis/Prince Andrew interview – there are two TV dramas, I think they’re in the can, one Netflix and one Amazon. A lot of writers think “oh, I had that idea!” That happens all the time.

All the time, I put something in and someone goes “oh, I know someone else who’s doing that”. Certainly happened with the Kenny Everett thing, someone else was writing a version. But you just have to think well, the version I want to tell is the one I want to tell; it’s mine. But it’s interesting; I just watched a wonderful film yesterday, American Fiction, and the main character’s a writer. Jeffrey Wright is just brilliant in it. And there’s one line he says, “I don’t feel like a writer at the moment”. You kind of constantly criticise yourself. Don’t be too hard on yourself – every single writer I know is extremely self critical.

So what then gets you to the finished product when you’ve had an idea?

I always work it up into a concept. I used to write whole scripts – I don’t anymore. I used to because I believed in the purity of the vision, the voices in my head. Possibly because I’ve learned the process of submission as a commercial writer, I kind of know the etiquette. For example, I wrote to 24 literary agents before I found one that would take me on. Each one of them had a very different form of submission. Some would require a full script, some a page, some a visual reference. It was incredible how disparate and variable they were. When I was an actor (again no scientific proof), you get maybe one in five jobs you audition for. As a writer, I think it’s one in ten. Your audition as an actor, you’re there for 5/10 minutes; your audition as a writer, you’re there for three months. You’re putting something down for sometimes years. For Best Possible Taste, from idea to principal photography was seven years. That’s fairly quick when you think somebody like David Seidler who wrote The King’s Speech, took 30 years from idea to being a BAFTA/Oscar winning film and a hugely lucrative project. But then you hear of other writers that go from job to job. I’m not like that. When I was younger, I thought the version that you sent out is the finished print, but I think even when it’s going out or I’m watching on TV or on stage, I think “I’ve got a rewrite bit”. It’s a bit late by then.

Am I a perfectionist? I suppose I am really, but I also learned – you have to learn to let go. When someone says it’s ready and I can perform that and I’m ready to direct that scene, everyone’s really excited; you let it go. Other people come into it then and then they change it, generally for the better. They imbue it with their context and their eye. You know, I just love it when actors ask me if they might change a line or change something here and there – because it says the same thing as the scene that I’ve written. It’s important to preserve the story and structure of that story. I’m not so proud about that anymore. I used to be really defensive about it, when you think, I spent months writing this scene, it’s wonderful. The stuff you think are your home runs aren’t always the ones that work on the stage. There’s that old adage: what works on the page might not work on the stage and vice versa. And I’ve written comedies thinking, “oh, that’s a homerun. I’ll get a big laugh on that”. And it’s met with the silence of all ages. And vice versa, I’ve written something I’ve thought was pretty average or run of the mill or trite, I’ll try it and it gets this huge wave of laughter… You never know until you put it up there. You’ve got to get your work seen, sniffed by, rattled by as many people as you can. And let it go. It’s hard. It is really hard.

How do you feel about watching your own work?

Oh, I loathe it. Are you kidding me? I absolutely loathe it.

[He thinks deeply, starting a couple of times but stopping. The first question which seems to stump him for a moment.]

Oh, gosh, that’s a really good question. On television, I very rarely watch what I’ve written. But by the time it’s on TV, you’ve seen the dailies, the assemblies, the rushes, you’ve seen the editors cut, the rough cut, you’ve seen the pre music and effects cut – so you’re pretty used to it. But there comes a point when you think, again, you’ve got to let it go. And it’s other people that do that bit to it. But certain shows I’ve written – I’ve never even watched my episode Marple on ITV. I watched Best Possible Taste because we all went round to the producer’s house. It was a lovely evening, we had pizzas and watched it trending for a little bit, which was lovely.

I think the worst part is theatre, because you can sit and watch. I’m thinking about the show that I did in Edinburgh. Generally the audience reaction was the same every day and there was, I promise you, a standing ovation at the end of every show. But there are bits in the show you think, “don’t drop the ball, don’t lose your concentration, audience. It’s alright. It’s gonna be alright, get through this bit”. So you feel it along really. And it’s quite nerve racking. I suppose, if you’re a good writer, I think it’s part of you, it’s part of your soul and your DNA and your creative vision. There’s nothing you can do, once you let it go. Unless you’re in it, of course, which I don’t want to do but in Lena, because we had to work hard to achieve the budget, I agreed to be in the band playing bass and guitar, and I could get to see the show from behind. I got to see all these amazing reactions. And even that was nerve racking. The only good thing about that was because I had to concentrate on what was coming next, then I had a distraction.

But my show Morecombe, which did really well for me, the actor playing Eric Morecombe was a guy called Bob Golding – total genius. He was Olivier nominated, and we won an Olivier for Best Entertainment on that. One evening, Bob was on stage and just before he went out he said, “Timmy, come and have a look”. There was a tiny little crack of light between the curtains and I looked through at this full house, three or four stories up. And in the second row is Michael Palin, who is absolutely one of my comedy heroes. I was simply not worthy. I think that was the moment I realised I didn’t really want to perform. Again, I knew exactly the reaction at the end of the show, but I still didn’t enjoy watching it because you care so much about it – it sounds really disingenuous, I’m not a parent, but it’s like putting a kid up there. You remember where you were as well. “I was on a train going through the Lake District when I wrote that scene” or “I met my friend in Glasgow when I thought about that”. You can smell it, it’s quite Proustian and it comes back to you.

I suppose it’s a deeply personal thing that becomes very public.

Absolutely. I suddenly realised when I said that, god, it’s been a long time since I just sat down and wrote something organically from my own consciousness and voice, and from my own love really, and I think that’s when I’m at my best as a writer. But at the same time, I know that it’s actually my job. I’m not a bread-head at all but I do like to turn it into a living. Am I defined by it? No, not really, but I do like the idea that I can fill a theatre or that I can actually tell my mum something’s on telly. It’s gratifying and satisfying as well because most of it comes back off the crossbar. Like I said earlier, for every 10 projects I put back out there, nine come back. But I also know that sometimes you can regenerate those in years to come. You can revisit those – nothing is wasted. But it can be quite daunting to think, looking back, gosh, I’ve pitched 60 projects in the last 10 years.

But when they do work, and you do get in you get an award for it – how does that feel for you? Is it nice to know that it is getting that recognition?

Yeah, I think… is it recognition? I suppose it’s satisfaction. I’ve never been to an award ceremony ever, ever, ever thinking I was going to win an award. And the very first time it happened, I was actually at work, performing the show. It was a BAFTA Award for the show with the Junior Television Workshop, it was called Your Mother Wouldn’t Like It, a kid’s sort of magazine-y, sketch-y show. It was really anarchic actually, it was great. And because I’d worked on that I was so proud of this fact and Ronnie Barker gave the BAFTA award to the producer and Peter brought it back from the ceremony and let everybody hold it, I sent the pictures to my mum. But it was sort of, if you like, justification for all those lonely nights, sitting there thinking “nothing’s coming out”. It wasn’t addictive. But I love what Steven Moffat said about how he comes down for breakfast and he sees the mask winking at him. But I do remember that day –

[Tim is talking about the day he won his Breakthrough Talent Award at the 2013 BAFTA Television Craft Awards – but is too humble to say it outright.]

I was working on what they call polishing and I remember going to the BAFTA Awards and thinking “I’ve got a splitting headache. They’ve put me right at the back of the hall. There’s no way I’m going to win this.” And then Russell Tovey was calling my name. I hadn’t honestly prepared a speech for it and I know most people say that. I was making it up as I walked across. So whatever I said was absolute drivel. But I think also, a little part of me always thinks, I probably did imagine this once, when I was writing through the 80s and 90s. And thinking, what if one day I actually had a chance to stand up and say generally to every writer in the world, I know how you feel? If I could do this, wouldn’t it be lovely if you could too and you can do it. And I do feel truly democratic about that actually. I remember I won a fringe first for my show Morecambe when it was at the Edinburgh Fringe. It took me days to actually read the award and it says on it, ‘awarded for innovation and outstanding new writing’ and I think, god, that means the world to me, you know. That it’s not a piece of metal or great plaque but actually, it’s what it represents. And that’s why I think I connect it with satisfaction, perhaps. It’s lovely furniture, don’t get me wrong, I don’t want to hand it back. But when I read that I thought wow, that’s what it’s for.

You’ve written about real life people who are very famous and beloved, and you’ve done it to great success. How did it feel knowing that you’re going to be dealing with somebody’s cherished childhood heroes?

I think one of my absolute beliefs as a writer is: there is more than sufficient in the truth, if you really work hard at the research, the immersion. If you push yourself to find out stuff – and believe me, I’ve walked this walk – you can find out a hell of a lot more by not going online. Some of the analogue ways to research things, to, literally, go through an old diary or a newspaper, to have a drink with somebody who was there or was on the periphery or the fringes of it, is beyond valuable. It is absolutely amazing what you can find, without having to just artfully transcribe a wiki page. I tend to get as close as I can to the subject. I’m really lucky because I’ve actually met an awful lot of the people I’ve written about. If I’m writing a biopic – I write other things as well, honestly –

[His mock eye-rolling indignation here catches me off-guard and makes me laugh a lot – it is true that he doesn’t write other things, also to great success.]

But my absolute note to self is to stay as close to the truth as I can, whilst obviously bringing in an element of dramatic licence; you have to do that otherwise, as I say, you can just read a wiki page on somebody. But I also really like the idea of telling the version, portraying the version of that character that I want to portray. One of the things that I loved about my play Lena is it appealed to really young people (The process of creating the play and story behind ‘Lena’ was followed for a documentary, accessible on BBC iPlayer). They discovered it themselves. I didn’t market it as a trip down memory lane, you know – this play deals in selfie culture, the inextricable link between self esteem and self image. So there was a causal link between something that happened in the 1970s and right now. Young people literally clustered around our lead, a brilliant actor called Erin Armstrong, and at first I thought she was meeting friends after the show, but then I heard the conversations and it was like an arrow through my heart. Suddenly you realise that eating disorders affect so many people, and even more so since Covid. The figures are bewildering – almost trebled over the last three years. It’s awful, and for a narrative to hit that part… suddenly, I wrote something that was historical, but very current. That’s a gift, because I don’t really want to write memories or good old days stuff. As long as it finds a currency and a contemporary appeal then I’m happy.

If you find the bigger, broader tropes and themes of what you’re really writing about, you’ll be surprised what it’s actually about. I remember in a workshop I went to in LA, we were all asked why we write and I said something like “Ohhh there’s a drum inside me that beats.” All this, you know, trying to be clever. And I looked round to this guy and he went “because I hate, a lot. Because I hate things” and I thought [Tim laughs] but I get it! You’re processing something that becomes a creative force, a force for good – I have avenged and revenged so many people that have upset me by putting them in plays. I can think of one particularly, it was a gift to the play. Because it was almost Greek…

The play that I mentioned earlier, The Sociable Plover, is set in a bird watching hide. I know about bird watching. I know that bird watchers can be horrible. Very proprietorial, aggressive, territorial – like birds. It’s two completely disparate male characters that meet by accident. One of them is a birdwatcher, the other one categorically is not. It happens over the course of two or three hours on a stormy afternoon on the Suffolk marshes. You could put on a play that would work in a sort of Peter Brook, black box style on a carpet at the pub, which I’ve done. It really sharpens you – if you can do it there, you can expand it. I worked with Richard O’Brien and I remember him saying that in the original Rocky Horror show, they had one microphone that they passed between the cast, a carpet and a ladder, at the Theatre Upstairs in the Royal Court. And you look at it now, it’s lights shining, lazers, it’s wonderful. But learning economy doesn’t mean being a cheapskate or lessening the potential of your production values. It just means barest bones of the story and finding a way of presenting it whereby it doesn’t need 400 extras or 15 bands or loads of dancers and wonderful lights. But that’s my way of doing it. When someone says “oh don’t worry Tim, we can make that happen.” you think oh gosh, I thought we had to do with the ladder and a mic.

Playwriting and screenwriting. How do they compare to you? Is it a different process?

It’s an entirely different process. I think they are two separate languages. I’ve learned that quite recently, because three of my plays have been optioned as films, which is lovely. This has all happened in the last, I would say, three or four years. They are in development. I think probably one or two of them stand a better chance than the other one but it is like going back to ground zero, point one. That suddenly what you have learned through the economy of telling the story on stage, you can broaden – I can write about you sitting in that chair, but I can’t read you thumbing the page of that notebook. But on film, it’s important that we see what you’ve written in the notebook, visually see it, and we can also score it so that it means something in your text. With film, because it’s a visual medium, you can actually tell the scene without any dialogue, if you’ve directed it well; if you’ve written it well to start.

With theatre, it’s a dialogue led medium. You do need to impart so much exposition. The three projects I’m talking about, one of them was commissioned not only as a stage play, but as a screenplay at the same time. As a film, I think it would open it up in terms of imagination and breadth of vision. Separate languages, but – storytelling. Imparting that story, invoking that process.

Do you have a routine that you follow strictly?

I’m really disciplined – in fact, most people laugh when I tell them that. A very successful TV writer I know as a friend said that he finds the 9 to 5 kind of approach to Creative Writing to be counterproductive. He’s highly intelligent, very successful – he said, “after four hours a day, I start to feel it’s a law of diminishing returns”.

You remember earlier when I said you need to be nice to yourself. And remember, taking breaks, all that, is really important. I don’t set myself a deadline. But I do understand that law of diminishing returns. I think it was Peter Mayle, a novel writer who wrote A Year in Provence, said (it’s a lovely bit of advice): “Always leave it when you’re happy with something. Don’t leave it on, I must fix this in the morning.” I’m paraphrasing, but today, it was a relatively simple the task at hand, but it’s such a complex story and it’s a torturous, involved love story, that I have to connect to the present day and I think most people just see it as “oh you just need to go and write this story about these two people”. Nooo! It’s really difficult as Chris Chibnall said, it’s really difficult. But, when you write a section that actually does not only mean something, but absolutely chime with your view of the project, your vision of that piece – right there, that’s it. I mean… the problem is that it has to be in tonight! But I did, I left it looking forward rather than thinking I can fix it in the morning, or I hate these people. Or, I hate myself.

The general theme we’re going for is, when we tie all of these interviews together, is sort of about the future and where you see the industry heading towards, so where do you see it in five years time?

That’s another great question because I have been asked about AI and things like that, for weeks and weeks now. I did a little Q&A when I was in Edinburgh (with the legendary Christopher Biggins) and that was the first question I was asked. I know another dear friend who’s a very successful pantomime producer, and he writes I think between eight to ten pantos a year, which is a heck of a lot of work. Interestingly – and I trust him implicitly – he put into ChatGPT or one of the AI things, ‘write a panto’. I think it was Aladdin. And I thought he was gonna say, “oh, gosh, it’s dreadful”. He said “you know what? It wasn’t that bad. I could finish it but – it wasn’t that bad”. And that is slightly –

[He makes a squeaky sound of concern, recognisable to all those trying to forge a creative career at times like these.]

But you’re talking about a tried and tested art. You’ve got to write something that isn’t traditional and there’s nothing AI can do about it. I’m such a fan of the human spirit and the human condition. I think that as long as there are people living life, then they can be written about. And actually, AI is never going to have a sense of humour. How could it possibly? And I think you need a sense of humour to articulate, to identify some of the characters that we’ve discussed and talk about some of the experiences that you had.

At the same time, I think there are so many more opportunities for young people now because when I started out there were probably four main broadcasters and yes, okay, the pie has got larger and the slices perhaps have got smaller, but to be able to write something for an imaginative producer like Netflix or Sky – their remit is amazing. You might not like everything they put out. But I think they’re incredibly courageous broadcasters. And I think there are opportunities outside of the mainstream for writers as well. Theatre is burgeoning. The Edinburgh festival came back up – it was 19% down on the money, but it’s still packed. I do think there’s a huge resurgence in the need for good entertainment. As soon as something comes along that’s great, something else comes along immediately behind it. Our appetite has become omnivorous.

I think it’s possible to have your voice out there as a creative writer. Some of the best writing that I’ve heard has been on podcasts – because again, people are free to write what they want or they’re not encumbered by traditional norms or censorship. I think a lot of people are quite worried about writing stuff that might be seen as inflammatory or offensive, or stuff like that. I’ve always felt like that, I don’t want to write a kiss and tell, something that upsets or offends anybody. You must always remember – people like to be entertained. I think in the last couple of years it has become a dirty word, entertainment, or certainly seems unfashionable to say. All the stuff I’ve mentioned now, it’s been, to me, very entertaining. But you don’t need to be worthy or have something. I don’t have a political voice in me at all. I don’t want to, but again, it might be unfashionable to say I want to educate, inform and entertain.

Have you seen anything recently that has excited you?

The Motive and The Cue, I came out tap dancing from the theatre, it was so good. Jack Thorne has written a fantastic script. It connects, it’s emotional, it entertains, all that stuff. It teaches – that, I thought, was wonderful. I particularly enjoyed a little English film called Scrapper. I think the director is wonderful, I think it’s her first film actually. Again, really honest, great imaginative filmmaking, but the writing is beautiful. And the kid is genius – she’s absolutely brilliant. I’ve been to all the big blockbusters, but I come slightly “meh” from them. Having said that, I think American Fiction, you should watch that as a writer because it’s about a writer and a writer’s lot. It’s really interesting that it flips so many stereotypes on their head. Debunks so many stupid myths. It’s a really clever piece of writing and it’s a difficult subject to get right. It’s a brilliant performance.

I probably waffled on. Well I think ultimately – this sounds so simplistic but – you’ve got to be true to yourself. And I have been. I took a massive chance because I had a really good career as a performer. I just kept working. I never stopped. And it wasn’t even quiet confidence or resolution. It was just something that I had to do otherwise I would have felt defeated had I not said in 1998, 99: “I just want to write”. My idea of a sabbatical would be to work something, actually put something together that I love. And actually don’t give yourself a hard time about “oh, gosh this could be a vehicle at the national, I hope I get a TV deal on this”, because, in a way, that’s what it has become. It’s become a profession, a vocation – I’ve turned it into a paid job. I’ve met a lot of writers who have had maybe one success, and it’s looked after them for their whole lives. Richard O’Brien, with Rocky Horror. He told me once there were 400 live licences at any one time, throughout the world. I remember saying, I’d like to write a cult television drama, a cult theatre drama and a cult movie drama. And I have, I mean, they’re tiny, but they’re still things I wanted to do. And is it Empire building? Is it something I think, “bigger and better”? No, not at all. I’ve got a commission for community theatre in Lancashire this year. I’m really happy to do it; it’s exactly the same advocation, care and drive that gets me to the last page.

Tim finishes our discussion in typically generous spirit – by asking me about my own experiences on the MA Screenwriting course. We chatted for around 3 hours and I left our chat with the one overwhelming feeling that I’m sure will fuel me for some time: sure, it’s not easy, but with the right mindset, Tim makes it feel as though it’s all possible.

https://www.featherproductions.com/

More information about the production company Tim runs with his partner Anna can be found here, on their website.

Leave a comment